At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Navajo were wealthy and successful pastoralists, with orchards, irrigated fields, and large herds of livestock.

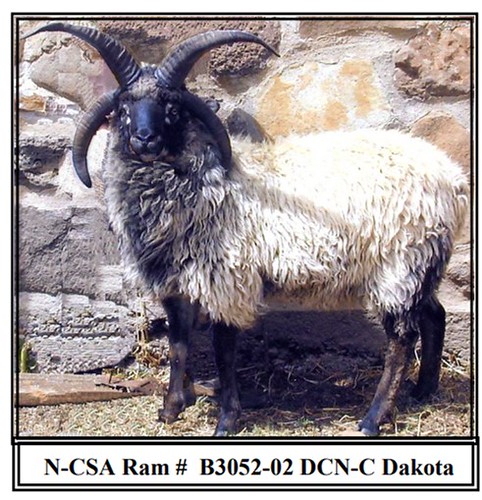

The latter were primarily Churra-type sheep, now called Navajo-Churro sheep, originally obtained by raids and by trading with Spanish colonizers.

In 1846, with the encroachment of American settlers on Navajo lands, that way of life was brutally disrupted. Kit Carson’s militia viciously terrorized the Navajo, burning orchards, destroying crops, and killing sheep, culminating in The Long Walk of 1864-1866 during which nearly 10,000 Navajo people were forced to march on foot more than 300 miles to an American internment camp at Fort Sumner/Bosque Redondo.

Some Navajo were able to escape the roundups by hiding in canyons and other remote areas. Amazingly they were also able to hide small herds of Churro sheep, a sure-footed and hardy breed that was well-suited to survival in tough environments.

After four years as “prisoners of war,” the Diné returned home and began to rebuild both their herds and their Nation. By 1890 the Diné reportedly already had 1.6 million sheep and goats.

Between 1870 and 1930, the Diné population quintupled, thanks in part to a protein-rich diet of lamb and mutton. Given that this is the period during which the overall population of Native Americans in the United States reached an all-time low, it was a remarkable achievement.

Sadly this period of rebuilding would lead to more pain and frustration for the Navajo people. When Navajo lands began to show signs of environmental distress, federal agents attributed this to overgrazing, and refused to listen to competing theories of cause. We now know from tree-ring data that the primary factor was climate change: a decades-long dry spell, followed by an unusually wet period.

“This dry-then-wet pattern encouraged arroyo erosion and sand-dune formation—a geomorphologic cycle that had happened many times before in this sandstone-dominated landscape.”

The huge Navajo herds of goats, sheep, and horses certainly did not help. But what followed was a catalogue of abuse in the name of “the environment.” The Bureau of Indian Affairs instituted a herd reduction program from 1933 through to the mid-1940s. Heavy-handed federal interventions included indiscriminate slaughter of Navajo livestock, and mandated maximum herd sizes, all without adequate compensation.

As described in “A Short History on Navajo-Churro Sheep” by Diné be’iiná

“Government agents went from Hogan to Hogan, shooting a specified percentage of the sheep in front of their horrified owners, who love their sheep and regard them as family members. First to be shot were the Churro, because the agents thought this hardy breed was ‘scruffy and unfit.’ Today, elders tearfully recall that time and can describe in detail each sheep that was killed and the exact location of the massacre.”

Not surprisingly given the flawed understanding of the causes behind the deterioration, and the draconian way in which herd reduction was implemented, range conditions only worsened, the reservation reached an ecological tipping point, and by the end of the program, to quote historian Jared Farmer,

“the tribal economy was in ruins. Unemployment, indebtedness, poverty and alcoholism ravaged Diné Bikéyah.” The legacy of the US Government’s destructive “reservation” program persists to this day. The Navajo are a nation of 175,000 people in 46,000 households, primarily in the state of Arizona – I quote US not for profit Prosperity Now:

“The basic needs of residents within the Navajo Nation are not met: 35% of residents do not have access to running water, 15,000 people do not have electricity and residents must drive for hours in order to reach the nearest hospital or grocery store” – not to mention water supply. Some 35.8% of Navajo households have incomes below the federal poverty threshold, compared to 12.5% for Arizona as a whole. One in two do not have sufficient liquid assets to subsist for three months without income; and they have higher rates of chronic illness, lower life expectancies, and lower rates of insurance than the national average. Less than 9% of the Navajo population over the age of 25 have had the opportunity to access a four-year college degree, compared to 30% for Arizona as a whole, and 16% are unable to find employment, compared to a state average of 5%.

In the last two years, with the COVID pandemic raging through the world, the Navajo Nations people have lost a lot of people and lots of churro sheep lost their shepherds. More and more , everybody who is involved as a farmer or trying to make a living with creating fibre, are told by big industry that some rare breeds, like the Navajo Churro, are unsuitable and have no place in the national or global market.

I am just going to say that right here and right now as I have always done…this stance the big industry is taking, in my humble point of view, is total and absolute BS.

I can say this of course because I have never ever listened to so called “GLOBAL” industry or even bigger processing companies, who always want to steer a breeder towards something that is easy to process and fast.

Our perception , even as crafters, has been extremely influenced by their view that everything needs to have a white base (One colour to process is easier than a few mixed colours because every time the machines need to be cleaned etc etc), needs to be fine (but not too fine because if it is too fine some machines cannot take it either and it has to be wooshed off to Italy to be processed…talk about “the Goldie lock “ principle , well that is it isn’t it?)….. Whereas I, as a weaver, spinner, dyer and breeder, love the diversity of colour.

The way that the dye plays with fleeces that have different colours going through them is like how sunlight and shadows play with what we see in nature. Definitely much more interesting than a “flat white”.

Strangely enough, I have found in my 18 years of trying to make a living from my fibre art, that big industry is trying to copy what handspinners have been doing for a long time: spin yarn that have a more “natural” look or spinning so called “zebra” yarns (different shades of white and grey and black)… But I digress…..lol Back to the struggle of the Navajo People and the Churro sheep:

In 2019, a handful of Diné shepherds felt lucky to be paid 1 to 5 cents per pound for their Navajo-Churro wool; others weren’t as fortunate. “Our Navajo-Churro wool was kicked away,” said one Navajo shepherd , as tears fell down his cheeks. “The traders tell us our wool is worthless and that we need to start crossing our sheep with fine wool rams.” We can make a difference as crafters and artists! Not only can we help by helping the small farmers survive and letting rare breeds with all their different qualities survive, but also say to the big, unsustainable and wasteful fashion industry, that we are not falling for it anymore.

Support small farms, support diverse culture, share and create.

Please don’t let anybody tell you that everything needs to be super fine and soft for it to be beautiful or useful: I call that fibre racism.

So much beauty can be made from rare sheep breeds. And, so much history can be lost by dismissing their fleece and the shepherds who take care of the sheep.

Things are starting to change. Navajo co-ops are starting with small processing mills and selling their own yarns.

Small and sustainable has always been my philosophy as well. It is part of who I am and my ancestors speaking through me.

I have recently gone through some very old albums and found some beautiful old photos, some more than 100 years old. Here are some I gladly share with you.

my mum at the loom

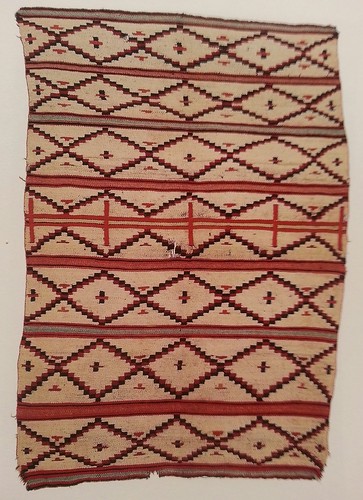

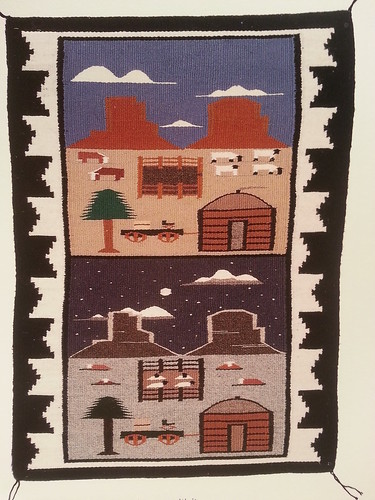

Navajo rugs take a loooong time to make.

Lots of them are sold by traders, while the weavers themselves are not given the money needed to survive.

There is a wonderful initiative : the adopt an elderorganisation, who does not only support those who are doing it extremely tough but also provide them with the opportunity and funds to keep telling their stories.

If you would like to purchase a handwoven Navajo Rug, please check out their website here:

https://www.anelder.org/Navajo-Rugs-and-Jewelry

So, what exactly is a Navajo Churro breed sheep? : The Navajo-Churro sheep is a small, long tailed sheep with a double coat of wool. The locks are long, tapered and open. Legs and faces of adults are free of wool. The sheep have a strong flocking instincts and are very intelligent. Most Navajo-Churro are a-seasonal breeders and mature early so two lamb crops per year are likely if rams are left with the ewes year round. The ewes lamb easily and are fiercely protective. Twins and triplets are not uncommon. Ewes seldom require assistance of any kind in lambing. Both ewe and lamb seem to know each other instantly. The lamb suckles within 10-15 minutes and is ready to travel by the mother’s flank within that same short time. These sheep with their long staple of protective top coat and soft undercoat are well suited to extremes of climate. The Navajo-Churro is highly resistant to disease, and although they respond to individual attention, they need NO pampering to survive and prosper.

The hand dyed tops that I am offering you here are blends of the undercoat of the Churro sheep it makes for the most wonderful yarn, suited for socks and outerwear as well as sweaters.

It is easy to spin and also beautiful to weave with to tell your stories. The wool is classified as “coarse” but that needs a bit of explaining !

The Navajo sheep fleece is composed of 3 distinct types of fibre: inner coat, outer coat and kemp. The fleece is open and has no defined crimp. The inner coat measures 6 to 12cm and generally ranges from 10-35 microns while the outer coat 12cm-24cm″, and is generally above 35 microns.

The tops I have on offer tonight range are an amazing 23microns and have a gentle sheen.

Axéhéé (thank you in Dineh language) for your support!

Have lots of fun exploring all the new fluff and fun stuff on the shop! There are always new tops, spindles and tools added all the time, not only Fridays , so please keep an eye out ! Also, when you would like a certain colour or colourway and you see it has sold out or has never been offered, please contact me : always happy to enable. This goes for spindles as well ! Paul is more than happy to create a custom spindle just for you ! Anything goes !

Have a wonderful weekend and happy creating !

Big hugs

Charly

the spirit line (close up)

the spirit line (close up)